The problem with peer review today is that there is so much research being produced that there are not enough experts with enough time to peer-review it all. As we look to address this problem, issues of standards and hierarchy remain unsolved. Stevan Harnad wonders whether crowd-sourced peer review could match, exceed, or come close to the benchmark of the current system. He predicts crowdsourcing will indeed be able to provide a supplement to the classical system, hopefully improving efficiency and accuracy, but not a substitute for it.

The problem with peer review today is that there is so much research being produced that there are not enough experts with enough time to peer-review it all. As we look to address this problem, issues of standards and hierarchy remain unsolved. Stevan Harnad wonders whether crowd-sourced peer review could match, exceed, or come close to the benchmark of the current system. He predicts crowdsourcing will indeed be able to provide a supplement to the classical system, hopefully improving efficiency and accuracy, but not a substitute for it.

If, as rumoured, Google builds a platform for depositing un-refereed research papers for “peer-reviewing” via crowd-sourcing, can this create a substitute for classical peer-review or will it merely supplement classical peer review with crowd-sourcing? In classical peer review, an expert (presumably qualified, and definitely answerable), an “action editor,” chooses experts (presumably qualified and definitely answerable), “referees,” to evaluate a submitted research paper in terms of correctness, quality, reliability, validity, originality, importance and relevance in order to determine whether it meets the standards of a journal with an established track-record for correctness, reliability, originality, quality, novelty, importance and relevance in a certain field.

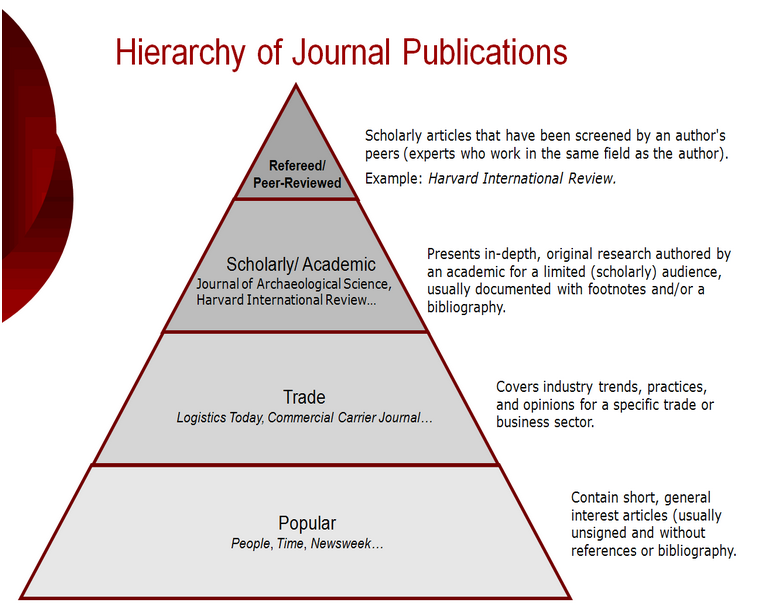

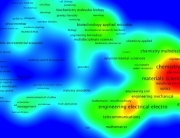

In each field there is usually a well-known hierarchy of journals, hence a hierarchy of peer-review standards, from the most rigorous and selective journals at the top all the way down to what is sometimes close to a vanity press at the bottom. Researchers use the journals’ public track-records for quality standards as a hierarchical filter for deciding in what papers to invest their limited reading time to read, and in what findings to risk investing their even more limited and precious research time to try to use and build upon.

Sifting for quality. Image credit: Precious stones by Enric (Pixabay, Public Domain)

Sifting for quality. Image credit: Precious stones by Enric (Pixabay, Public Domain)

Authors’ papers are (privately) answerable to the peer-reviewers, the peer-reviewers are (privately) answerable to the editor, and the editor is publicly answerable to users and authors via the journal’s name and track-record.

Both private and public answerability are fundamental to classical peer review. So is their timing. For the sake of their reputations, many (though not all) authors don’t want to make their papers public before they have been vetted and certified for quality by qualified experts. And many (though not all) users do not have the time to read unvetted, uncertified papers, let alone to risk trying to build on unvalidated findings. Nor are researchers eager to self-appoint themselves to peer-review arbitrary papers in their fields, especially when the author is not answerable to anyone for following the freely given crowd-sourced advice. And there is no more assurance that the advice is expert advice rather than idle or ignorant advice than there is any assurance that a paper is worth taking the time to read and review.

The problem with classical peer review today is that there is so much research being produced that there are not enough experts with enough time to peer-review it all. So there are huge publication lags because of delays in finding qualified, willing referees, and getting them to submit their reviews in time. And the quality of peer-review is uneven at the top of the journal hierarchy and minimal lower down, because referees do not take the time to review rigorously.

The solution would be obvious if each un-refereed, submitted paper had a reliable tag marking its quality level: Then the scarce expertise and time for rigorous peer review could be reserved for, say, the top 10% or 30% and the rest of the vetting could be left to crowd-sourcing. But the trouble is that papers do not come with a-priori quality tags: Peer review determines the tag.

The benchmark today is hence the quality hierarchy of the current, classically peer-reviewed research literature. And the question is whether crowd-sourced peer review could match, exceed, or even come close enough to this benchmark to continue to guide researchers on what is worth reading and safe to trust and use at least as well as they are being guided by classical peer review today.

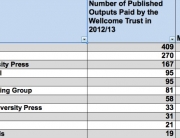

Image credit: Hierarchy of Journals SUNY Geneseo

Image credit: Hierarchy of Journals SUNY Geneseo

And of course no one knows whether crowd-sourced peer-review, even if it could work, would be scale-able or sustainable.

The key questions are hence:

- Would all (most? many?) authors be willing to post their un-refereed papers publicly (and in place of submitting them to journals!)?

- Would all (most? many?) of the posted papers attract referees? Competent experts?

- Who/what decides whether the refereeing is competent, and whether the author has adequately complied? (Relying on a Wikipedia-style cadre of 2nd-order crowd-sourcers [pdf] who gain authority recursively in proportion to how much 1st-order crowd-sourcing they have done — rather than on the basis of expertise — sounds like a way to generate Wikipedia quality, but not peer-reviewed quality…)

- If any of this actually happens on any scale, will it be sustainable?

- Would this make the landscape (un-refereed preprints, referee comments, revised postprints) as navigable and useful as classical peer review, or not?

My own prediction (based on nearly a quarter century of umpiring both classical peer review and open peer commentary) is that crowdsourcing will provide an excellent supplement to classical peer review but not a substitute for it. Radical implementations will simply end up re-inventing classical peer review, but on a much faster and more efficient PostGutenberg platform. We will not realize this, however, until all of the peer-reviewed literature has first been made open access. And for that it is not sufficient for Google merely to provide a platform for authors to put their un-refereed papers, because most authors don’t even put their refereed papers in their institutional repositories until it is mandated by their institutions and funders.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Stevan Harnad currently holds a Canada Research Chair in cognitive science at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and is professor of cognitive science at the University of Southampton. In 1978, Stevan was the founder of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, of which he remained editor-in-chief until 2002. In addition, he founded CogPrints (an electronic eprint archive in the cognitive sciences hosted by the University of Southampton), and the American Scientist Open Access Forum (since 1998). Stevan is an active promoter of open access.

Harnad, S. (1998/2000/2004) The invisible hand of peer review. Nature [online] (1998), Exploit Interactive 5 (2000): and in Shatz, B. (2004) (ed.) Peer Review: A Critical Inquiry. Rowland & Littlefield. Pp. 235-242.

Harnad, S., Carr, L., Brody, T. & Oppenheim, C. (2003) Mandated online RAE CVs Linked to University Eprint Archives: Improving the UK Research Assessment Exercise whilst making it cheaper and easier. Ariadne 35.

Harnad, S. (2010) No-Fault Peer Review Charges: The Price of Selectivity Need Not Be Access Denied or Delayed. D-Lib Magazine 16 (7/8).

Harnad, S. (2011) Open Access to Research: Changing Researcher Behavior Through University and Funder Mandates. JEDEM Journal of Democracy and Open Government 3 (1): 33-41.

Harnad, Stevan (2013) The Postgutenberg Open Access Journal. In, Cope, B and Phillips, A (eds.) The Future of the Academic Journal (2nd edition). Chandos.

[…] The problem with peer review today is that there is so much research being produced that there are not enough experts with enough time to peer-review it all. As we look to address this problem, iss… […]

Interesting to think of the current peer review model as facing a problem of scale. I hadn’t considered this before. I wonder about the extent to which the current cadre of academic workhorses — i.e. post-docs — are being relied on to bolster peer review capacity (either directly or indirectly).

Also, one other question for your list of five: What evidence is there that the current hierarchies in the current peer review mechanism wouldn’t simply be replicated in a crowd sourced model? The crowd is, after all, a social construct.

Indeed interesting, thanks! I believe, however, that this does not go to the root of what peer review is as an object of study. To propose complementary of ‘crowd-sourcing’ with the ‘current system’ is not understanding underlying relational dynamics in peer review that involve many structural properties (i.e., anonymity, access to judgements and decisions, temporality of review, access to the original manuscript). Forms of peer review that are post-publication and open to wider audiences are currently being used at several journals including at some 10 journals in the Copernicus suite of journals (see papers by U. Poeschl) and at the journal the Winnower. I have published a series of preprints on how we can investigate journal peer review as a scientific object of study and do away with assumptions that plague deeper understanding… see http://peerreview.academy.

The present peer review system is entirely broken, apart from a few specialist journals. In future all publications should be open access and they should all have an open comments section following the paper. The comments might need a bit of moderation to weed out obvious trolls. Sites like PubPeer have already shown that high quality post-publication review is possible. During the transition it might be necessary to have pre-publication review too. But my guess is that eventually that will become redundant.

Perverse incentives imposed on academics have resulted in a torrent of papers, many of which are mot very good, but all of which end up being published in a “peer-reviewed” journal of some sort. That will be disastrous for the reliability, and for the reputation of science if it’s allowed to continue as it is.