Costume and set designer Natacha Rambova attracted an unusual amount of media scrutiny during the 1920s. She became a high-profile celebrity whose private and professional life received a level of public attention usually devoted to stars. A multi-talented figure (designer, dancer, producer, screenwriter, actress, and playwright), she is the subject of feminist scholarship and appears in the Women Film Pioneers project at Columbia University. [1] As yet there are no in-depth studies of her career, but her striking designs have been appraised in analyses of the films to which she contributed, and are acknowledged in revisionist feminist histories. [2] In the absence of reliable primary documentation relating to Rambova and her work, conclusions are drawn from secondary materials such as press, journal and trade paper accounts that build a fictional persona for her – a brand identity, as we might put it. [3]

These stories, which are often industry gossip, or are generated via promotional operations, are the sources used by historians, biographers, scholars, and fans to weave narratives that become received wisdom and form the basis for evaluations of Rambova’s output. This is not unusual for research into areas where archive documents that provide verifiable information are scarce. Historians acknowledge the cultural significance of extra-filmic phenomena even though they may be circumspect about their veracity. However, in spite of the prominence of visual design in many promotional and journalistic materials, detailed examination of its role in creating characters and backstories for historical personalities is relatively rare. When visual elements are addressed, they generally come second to the written word, or are at the service of ideological analysis. In what follows, I focus on the relationship between design and performance manifested in media items, looking at the use of pictorial elements to project Natacha Rambova’s public persona.

While devoting space to Rambova’s life story and achievements, I shift attention to the ways in which her identity is fabricated through images and written texts circulating in the period. I argue that the self-presentation evident in such artefacts can be regarded as off-screen performance, and I extend the notion of performance to suggest that it is actively led by design. In his pioneering work on presentation of self in everyday life, Erving Goffman outlines the performance techniques adopted by individuals and groups to control perceptions of themselves in social situations. He relates these practices to theatre stagecraft, pointing to the importance of setting, costume, and props in creating characters and stories for individuals. [4] Goffman is concerned with person-to-person interaction, but his emphasis on impersonation as the primary means of identity projection is in tune with my project.

For Goffman, impersonation relies on repeated patterns of coded behaviour to stabilise identity definition, and he hints at the importance of design in this process, listing “clothing; sex, age and racial characteristics; size and looks; posture; speech patterns; facial expressions [and] bodily gestures” as part of the performance repertoire. [5] He sees identity as a mask that corresponds to how individuals wish to be seen, rather than as a true indication of personality. Other scholars have mobilised psychoanalytic concepts of masquerade to argue that the artifice of impersonation has the potential to denaturalise accepted social identities. [6] The focus in such research on cultural, discursive manifestations of identity, and the performance components that support or undermine them, informs my approach. The period in which Rambova lived and worked was typified by masquerade and mutable identities. Her character and backstory were forged through materials such as photographs, illustrations, and film stills that highlighted theatricality, artistic design, and role-play.

Design was prominent in early twentieth-century American culture, and modernist movements such as German Expressionism and Art Deco had a considerable impact on the developing cinema. European art films influenced the look and style of American productions striving for cultural credibility and targeting sophisticated audiences. The preoccupation with design was evident in film magazines. Motion Picture Magazine, for example, ran pieces on the contribution of renowned artists to scenic design and displayed signed paintings of stars on its covers. The magazine addressed style-conscious readers through artistic page layout, photo galleries and ornamental graphics. [7]

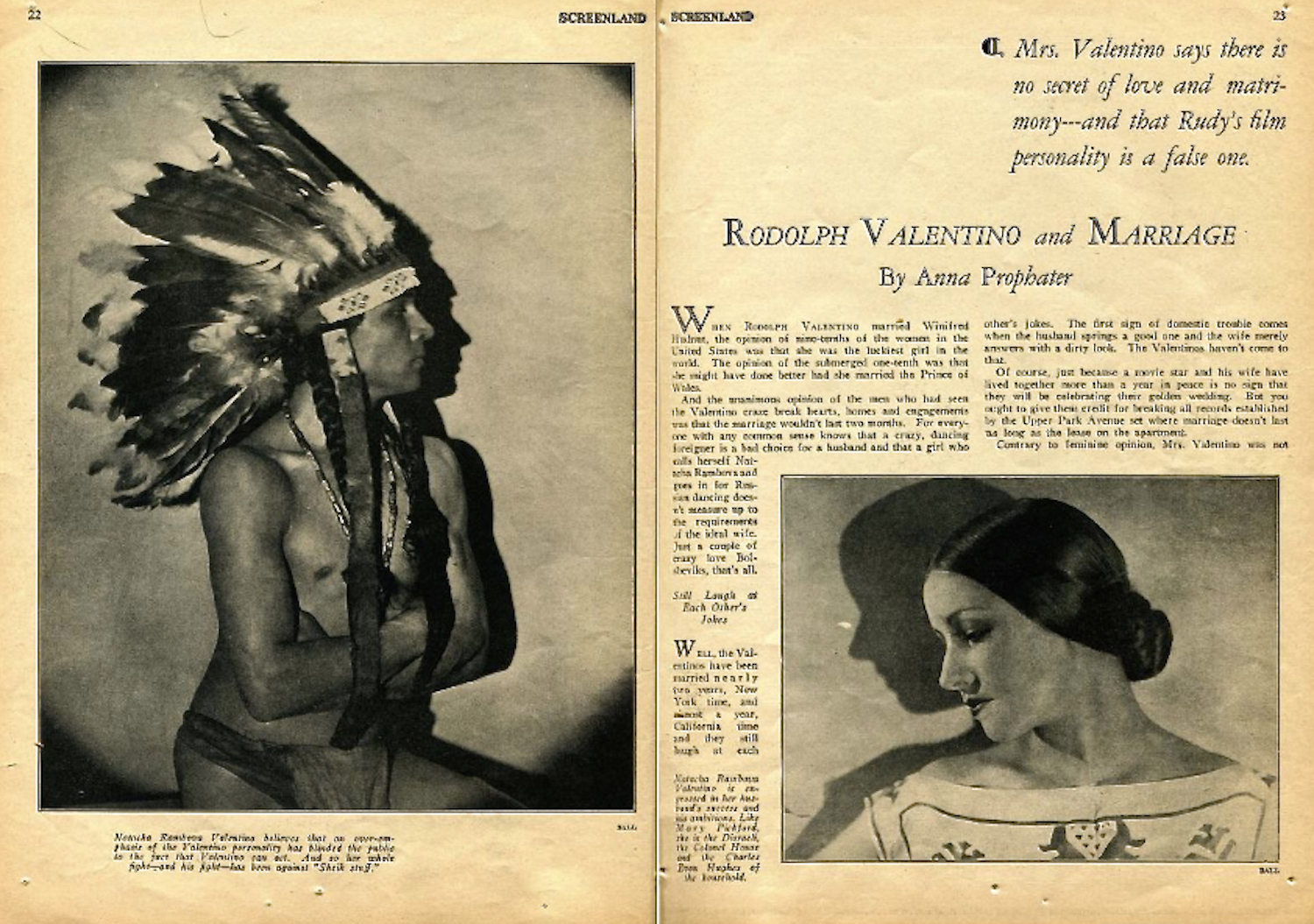

Performance was also significant in film culture. The fluidity of gender, class, sexual, ethnic, and racial identities was acted out in carnivalesque events and costume parties that celebrated the counter-cultural momentum of orientalised society. [8] In this feminised environment, women audiences and filmmakers became increasingly important, at least for a while, as stereotypes were challenged. Rambova participated in this performative activity in a number of ways, securing her reputation as a leader of style and a creative force. She is widely recognised as one of several influential women in the film industry who had an impact on the career of Rudolph Valentino, to whom she was married for a short time. They were frequently photographed together in shots that accentuate role-play and masquerade. Rambova often posed in ethnic costume. In an undated and unattributed photograph, her clothes and hairstyle suggest Native American Indian (figure 1).

The image may have been linked to the series of 1922 photographs in which Valentino posed as Black Feather, a Native American Indian whom he believed to be his spirit guide. Two of these, attributed to Russell Ball, appeared in Screenland magazine, unrelated to the accompanying article on Rambova and their marriage (figure 2). Rambova is sometimes credited with styling such photographs of her husband. [9]

One of the notable aspects of these portraits is the emphasis on impersonation. Valentino and Rambova are shown mimicking ethnic identities through costume and stance. Ethnic masquerade was common in the art and glamour photographs that appeared in upscale publications such as Shadowland, and in popular fan magazines such as Photoplay. The photos are staged, costumed, lit and framed and the subjects are consciously posing with props. The role-play in such visual materials aligns with Goffman’s concept of identity as fictional self-presentation, and with the theories of masquerade noted above. The public personas of stars and celebrities are depicted as masks in stylised images that highlight the artistry of visual design and are often created by celebrated photographers. In many of these images, Rambova is pictured as an exotic, bohemian character, surrounded by the trappings of sophisticated, orientalised culture.

Redesigning Valentino

Despite her Russian pseudonym, Rambova was American, born Winifred Shaughnessy, a gifted ballet dancer who apparently changed her name to Natacha Rambova when, aged seventeen, she joined Russian dancer and choreographer Theodore Kosloff’s Imperial Russian Ballet Company in New York as dancer, designer, and seamstress. An admirer of Russian art and culture, she kept the name when she became a professional designer. Her relationship with Valentino is said to have begun during the production of Camille (1921), for which she designed sets and costumes. [10] After a false start involving bigamy charges from Valentino’s previous marriage, they married properly in 1923 and separated in 1925. In a 1922 article in Photoplay she comments that she is not sure whether to call herself Winifred Hudnut (her stepfather was the wealthy perfume magnate), Natacha Rambova, or Mrs Rudolph Valentino, but that Natacha Rambova is the name that most clearly expresses the person she thinks she is. [11]

The article endorses her choice of identity by stressing her Russian connections and her cultured background, and is accompanied by photographs showing her dressed in fashionable bohemian clothes in stylish interior settings. In one she sits reading a book. In another, positioned next to two examples of her “bizarre” costume designs, she poses with a long cigarette holder against a doorway that has Chinese paintings on either side. [12] The piece praises her beauty and elegance, but the primary focus is on her thoughts and feelings about her husband’s acting talent and his shabby treatment by Famous Players-Lasky.

There is a contradiction between the photographs, in which Rambova is pictured as an independent, intellectual New Woman, and the interview’s emphasis on her wifely role. She is alone in the images and her appearance is far from domesticated. Although there is no overt sense of friction, her persona comes across as multi-faceted. The implication that she plays different parts is confirmed by her self-presentation, which is staged for the camera. Her influence on Valentino is recognised at the end of the article, where she is described as “the outward and visible sign of [his] spiritual evolution [...] the symbol of his culture [...] the crystallization of his success.” [13] Rambova is presented as a talented figure in her own right who exerts a significant impact on his career by bringing culture and sophistication to their relationship. Although her power in this respect was short-lived, it is arguable that it was considerable and extended beyond that of mentor. Through her designs she reinvented Valentino, projecting his body as a mannequin for fantasies of liminal identities and gender inversion.

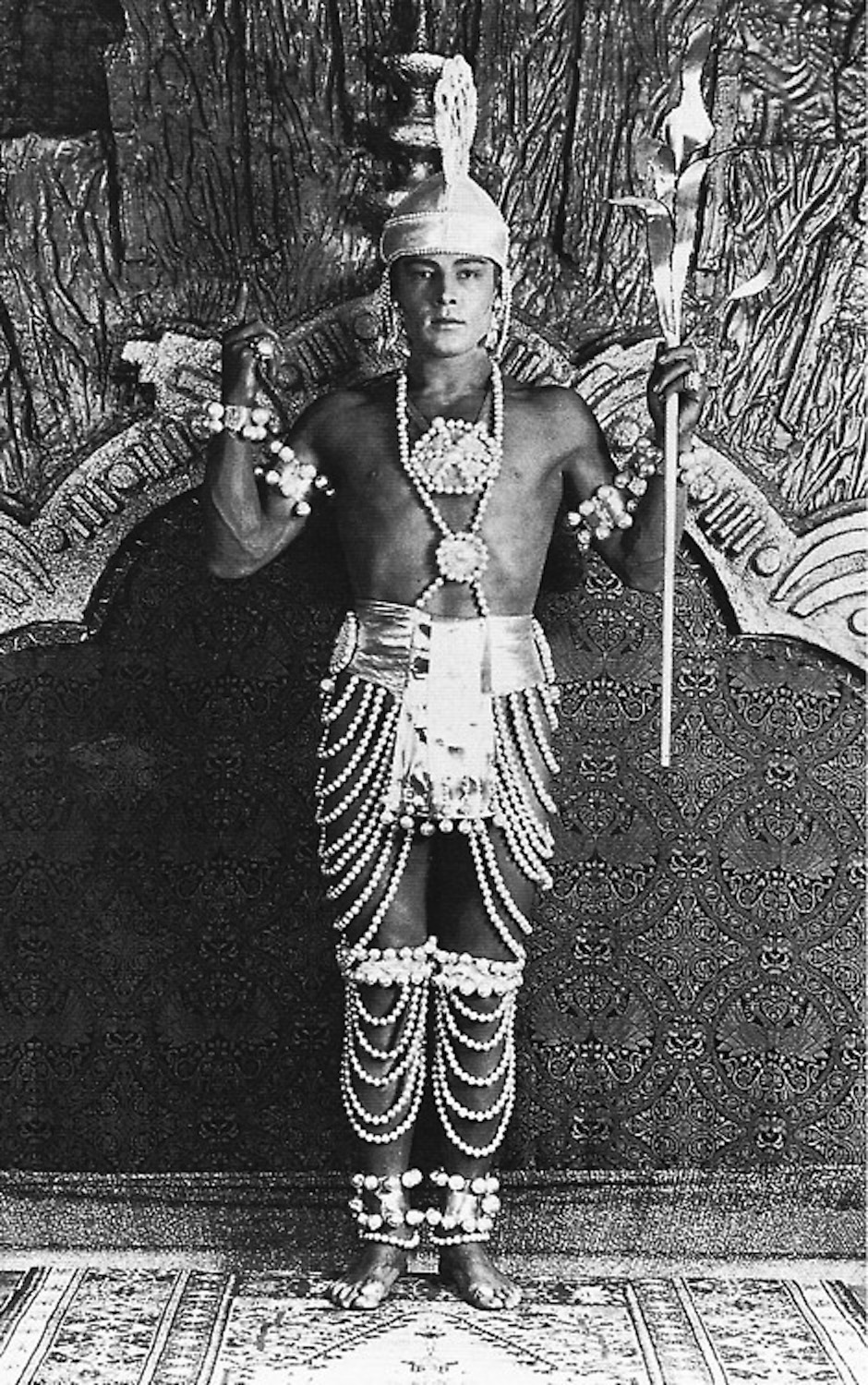

This is particularly evident in her work for The Young Rajah (1922). In her article on Valentino’s masculinity, “‘Optic Intoxication’: Rudolph Valentino and Dance Madness,” [14] Gaylyn Studlar includes an image of him draped in pearls for his role as the young rajah, design by Rambova (figure 3).

The term “optic intoxication” is a contemporary quote describing the perceived moral disintegration of dance culture, and the Valentino costume seems to epitomise the delirious excess conjured up by the phrase. It is almost too much for the eye to take in. Studlar refers to the gender, ethnic, and sexual ambiguity of the costume. [15] Valentino is feminised, orientalised and sexualised to a far greater extent than love interest Wanda Hawley, and is openly presented as erotic focus of the gaze. The design is extremely complex in its Orientalist setting and in the profusion of pearls, some of which are oversized. Valentino’s skin is darkened, and make-up emphasises the oriental appearance of his eyes. He wears earrings, a necklace, rings on his fingers and toes, and elaborate headgear. Even his phallic accessory has a decorative flourish. His right-hand forefinger points upwards in a pose reminiscent of Krishna, an androgynous, protean figure in Hindu religion and mythology. The image is almost risible in its overstatement. It asks to be interpreted, and it recalls the Ballets Russes designs by Léon Bakst for Nijinsky as the Golden Slave in Schéhérezade and as Krishna in Le Dieu bleu, in which the dancer’s appearance was scandalously feminised. The influence on Rambova of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and Bakst’s Orientalist designs, which she had seen in London in 1913, is much in evidence. [16]

Rambova’s use of pearls in The Young Rajah costumes is particularly interesting. Pearls were a feature of princely dress in British colonial India, where Valentino’s character comes from. For example, in a photograph taken at the Lafayette Studio in London on the occasion of a state visit, the bejewelled Rajah of Khetri displays the finery that signifies his prestige and status in the Empire (figure 4).

Figure 4 – Projecting empire: the Rajah of Khetri in princely dress, 1897. From the V&A Lafayette Negative Archive, http://lafayette.org.uk/khe1245b.html, © V&A.

Costume is paramount in presenting the sitter’s regal identity and otherness in relation to Western culture. Indeed, the image has the air of a museum exhibit viewed from a respectful distance. The lighting picks up the sheen and exquisite workmanship on his silk jacket, while his stance shows his accessories to best advantage. He appears to be modelling the outfit; this performance and the photographic style create a persona for him. It could be argued that the decorative garments, natural setting, and body language portray the subject as passive. Visualised from a British colonialist perspective, he is depicted in soft focus that renders him at once exotic, dignified and non-threatening.

It is possible that such portraits were among Rambova’s research materials for The Young Rajah. Some of the stills of Valentino as the young rajah imitate their style, and there are echoes of the princely costumes in Rambova’s designs. However, the element of impersonation is stronger in the Valentino shots. His stance and expression emphasise that he is acting, and the heightened gleam of his costumes makes them appear as a sexual fetish, especially those in which he is swathed in garlands of pearls. The costume itself becomes a focus of licentious desire, embodying the actor’s ambiguous allure in surface image. There is a level of irony in the exaggerated quality of the designs and the staging that produces a suggestive subtext: the masquerade itself is geared towards arousal, and the abundance of pearls contributes an aura of decadence. Valentino’s otherness, created by design, is offered up for aberrant pleasure.

Rambova’s use of pearls in The Young Rajah costumes reflected current tastes. Pearls were fashionable in the late teens and twenties, and it was common for female stars and celebrities to be photographed wearing strands of them. They were a sign of glamour and luxury and, because they originated in the East, had overtones of exotic sexuality. The jewel was a key feature of costumes worn by Orientalist vamps Maud Allan and Theda Bara in their notorious performances as Salome. Before the creation of cultured pearls in the 1900s, natural pearls were reserved for the very rich. In 1916, with the Japanese invention of cultured varieties, pearls became widely available. [17] The vogue for pearls was directed at women consumers, which makes Valentino’s costume more intriguing, and more opaque. Pearls have multiple connotations, from the spiritual to the sensual. In the latter case, they intimate female sexuality. In addition to the commodity fetishism incited by the pearls, the sight of Valentino adorned in female sexual symbolism would surely arouse conflicting desires and emotions in both male and female viewers.

In her chapter on fan magazine Orientalism, Studlar quotes Higashi’s extreme formulation of female consumerism and Orientalism as impassioned, “one of temptation, seduction and, finally, rape.” [18] Rambova’s Orientalist vision of Valentino as the young rajah suggests a reversal of this masochistic scenario. The androgynous costume destabilises Valentino’s image as a dominant male. The pearl chains emasculate him to an unprecedented degree; he almost looks shackled by them. There is a softening of his sexually aggressive persona in previous films such as The Sheik (1921), something that he and Rambova apparently wanted. [19] According to Valentino biographer Emily Leider, despite sequences in The Young Rajah that displayed the actor’s manly physique, critics did not appreciate the troubling inferences of his pearl-festooned vision of masculinity and compared his performance unfavourably with Blood and Sand (1922). [20]

Studlar calls Valentino a “woman-made man”, a description that does not necessarily exclude his appeal to male viewers. [21] As designed by Rambova, he is a complex and unpredictable phenomenon. The pearl costume renders him neither male nor female, neither Western nor Eastern – indeed, this is one of the points of The Young Rajah story. [22] The actor’s compensatory “virile display” does little to resolve this ambiguity. Writing about the cultural disturbances of cross-dressing, Marjorie Garber refers to Lacan’s formulation that masculine virile display actually appears feminine, and discusses Valentino as an exemplary case of unmarked transvestism, “at once feminized and hypermale”, citing Miriam Bratu Hansen to the effect that he was a male impersonator. [23] The emphasis in these formulations on performance and dress as producing the body and identity diverges from perceptions of costume as indicator of the body underneath as the site of a stable, known entity. If costume is regarded as a system of signification related to society’s sartorial languages and symbolic codes, it can be seen as defining and transforming the body. It not only plays an active role in producing performance, it also fashions the actor’s body in the service of an overall design concept. By foregrounding Valentino’s embodiment of the performative nature of identity, Rambova’s work epitomises this dynamic, productive role.

Valentino’s costumes before Rambova already had a strong emphasis on ethnic masquerade and exoticism (for example, the gaucho outfit from Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1921; his Arab robes in The Sheik; his matador and dandy garb in Blood and Sand). In many respects, Rambova drew on the vogue for Orientalism in US culture and Hollywood described by Studlar, much of which was driven by women. [24] At a time when female bodies were being reconfigured in the search for women’s social, cultural, sexual, and economic freedom, Rambova designed Valentino as the embodiment of the imaginary possibilities offered by Orientalism to the modern New Woman. While such fantastic visions were not untainted by conservative elements, they often ran counter to prevailing ideologies. [25]

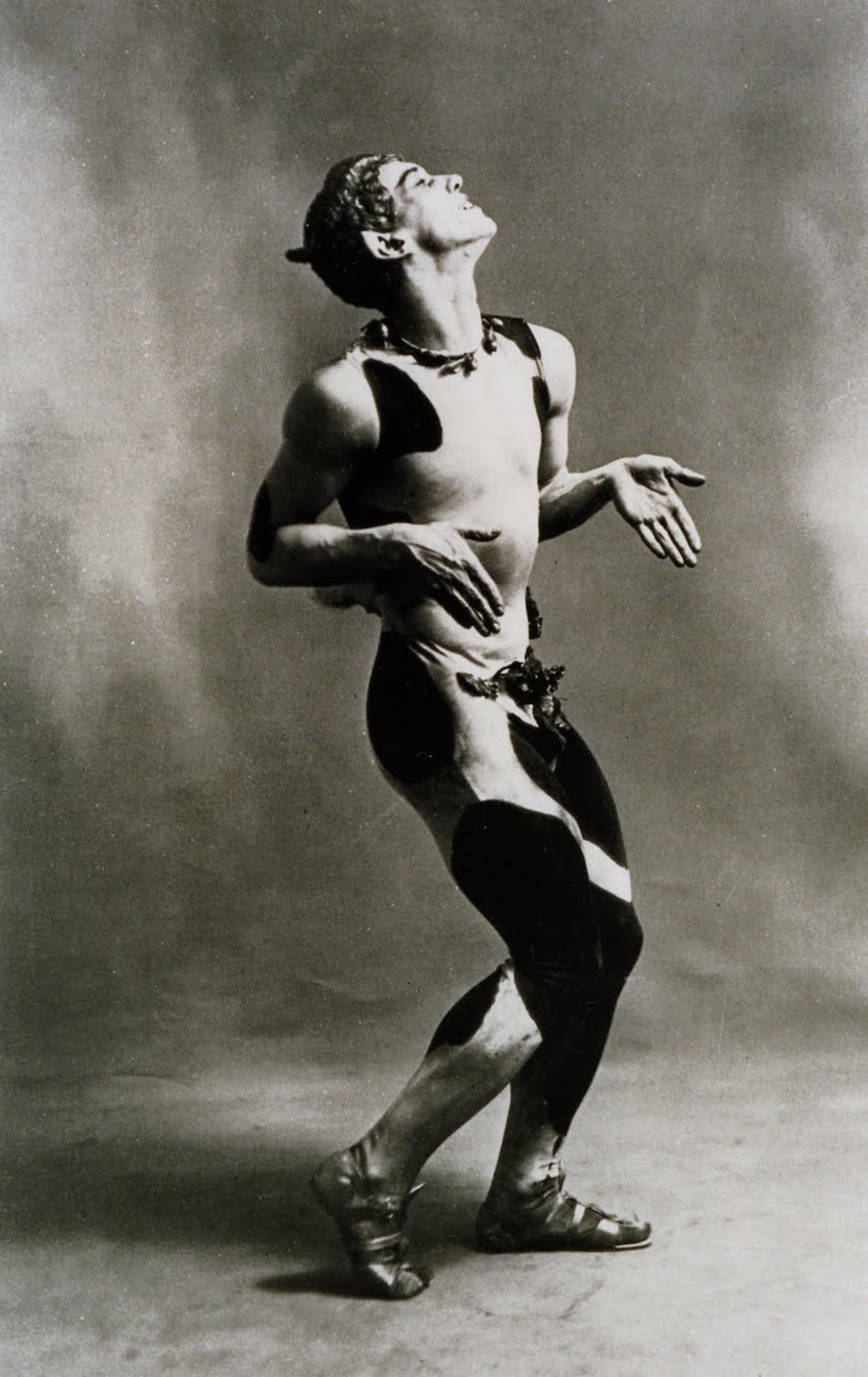

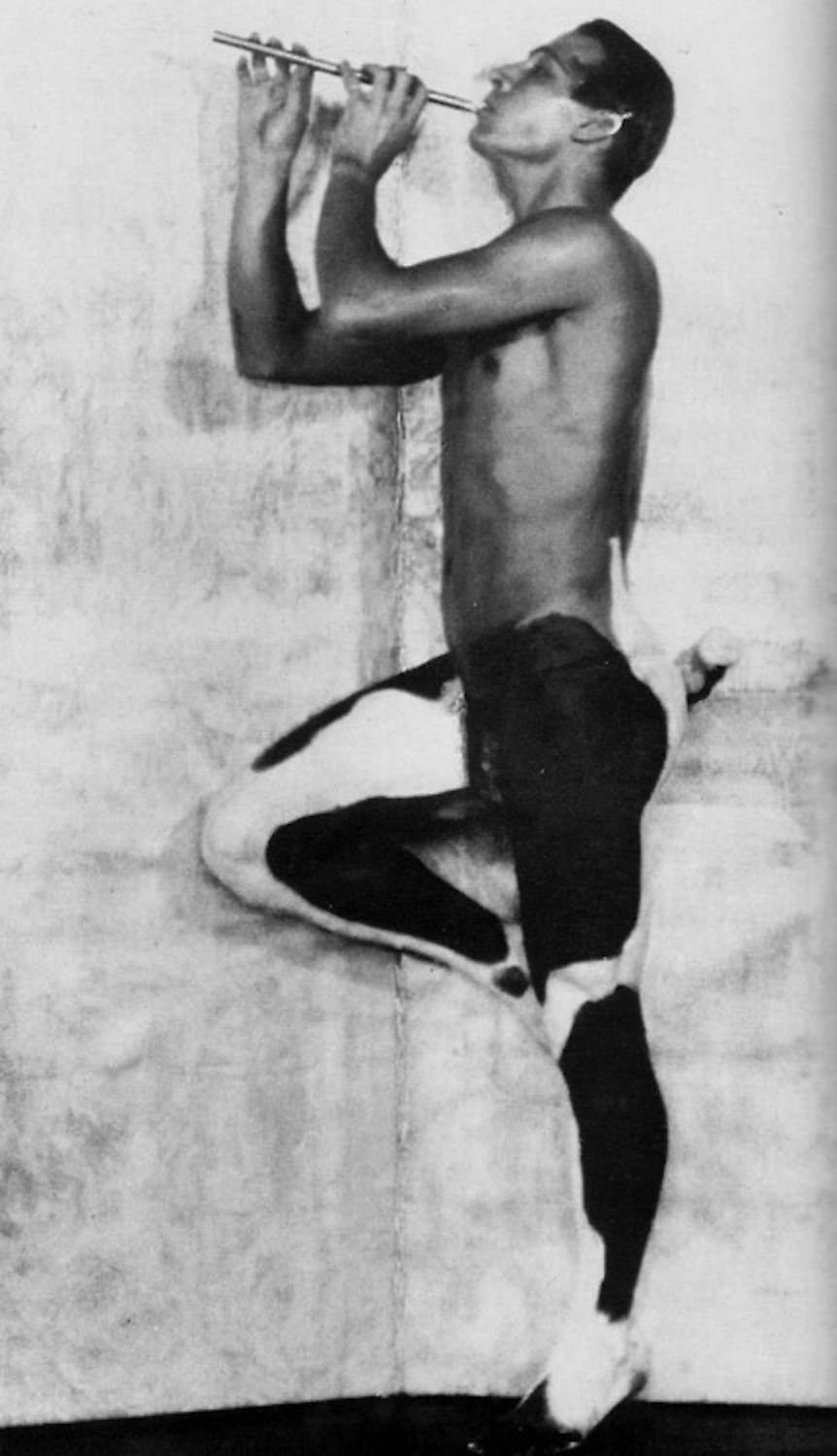

According to Leider, Rambova used Valentino as a canvas for her art. [26] Inspired by the outrage created by the Ballets Russes and fashion designer Paul Poiret, who dramatised from European perspectives the moral and sexual decadence associated with the Orient, she modelled Valentino in the image of Nijinsky in a series of studies by Helen MacGregor, staged by Rambova, which depict him as a faun (figures 5a and 5b).

Nijinsky’s revealing costume (left) was shocking enough, but Valentino’s was even more risqué. In the photo he is naked apart from a skimpy jock strap, and has black and white body paint simulating goatskin on his legs and feet. In a provocative touch, he has a stubby tail standing up at the back, a playful allusion to his masculinity. The homage to Nijinsky is only part of the story. The images also pay tribute to Adolph de Meyer’s photographs of the dancer, which had been published in limited edition in 1914. [27] The high-culture associations of the MacGregor photos aligned Rambova and Valentino with European art movements, but Rambova’s styling of Valentino in these images reinterprets the originals to produce a knowing commentary on his erotic appeal.

The Rambova-Valentino brand

Through her designs, Rambova projected an individual signature and a coherent persona with associations of European modernism that supported the brand identity of the Rambova-Valentino couple. She cultivated a sartorial style explicitly derived from French and Italian fashion designers and was photographed wearing Poiret and Mariano Fortuny. [28] She appeared in glamour shots by Arthur Rice and James Abbe that emphasised her exotic beauty, elegance, and distinctive look, and in portraits in which she was accompanied by props signifying high culture.

Figure 6 – New Woman: Natacha Rambova's highbrow persona. Photographed by Russell Ball: “Mrs. Rudolph Valentino,” Motion Picture Magazine, September 1924: 45.

In an image by Russell Ball from Motion Picture Magazine (figure 6), her costume and surroundings are orientalised and her stance is self-assured, as she looks into camera with one hand placed artfully on her hip and the other holding a Chinese figurine. The floral fabric draped over the chest next to her has overtones of Art Deco design. She is pictured as a highbrow version of the independent New Woman, not exactly a vamp, but certainly a force to be reckoned with. The caption draws attention to her married status, calling her Mrs Rudolph Valentino, and the text below the image celebrates her many talents, including her discovery of Helen d’Algy, who played opposite Valentino in A Sainted Devil (1924). On the opposite page there is a still of Valentino and d’Algy in character for the film, and a small inset portrait of d’Algy by Ira D. Schwartz. However, the Rambova photograph takes up the whole page and overpowers both, evoking through visual layout her authority and influence.

Portraits of Rambova and Valentino together are equally artistic, and they are often depicted as a matching pair (figures 7a and 7b).

In the portrait by Abbe, which has become emblematic of the couple, their similarity and androgyny is emphasised through their hair and bodies. In the other, by Russell Ball, Valentino wears an oriental-style robe that is echoed by Rambova’s turban. By presenting their subjects as mirrors for one another, these portraits reconfigure standard gender roles and hierarchies, resonating with discourses circulating in the period. [29] They also consolidate the celebrity couple’s brand, linking it with European modernism.

Rambova and Valentino identified themselves as European at a time when continental European art and culture was highly prized in Hollywood and in the US generally. The cultural exchange between Hollywood and Europe and the admiration for Hollywood films and actors among European filmmakers is well documented, as is the impact of European aesthetics on Hollywood films. European films were seen as the epitome of the art cinema to which many Hollywood producers aspired. Continental émigré artists, technicians, and performers were courted for their superior skills, while Hollywood offered them exceptional technical facilities. European style and design was in vogue and had considerable influence on North American culture and on Hollywood. Besides the impact on film aesthetics, it affected the sartorial choices of stars and other filmmakers, who frequently wore custom-made clothes from Europe. Like many other male actors, Valentino, a fashion icon in his own right, was fond of British design when it came to suits. Nevertheless, Orientalism was never far away: even when dressed European-style, he often displayed the ‘slave bracelet’ designed by Rambova, which he continued to wear after they separated.

Rambova and Valentino travelled to Europe regularly to buy clothes and collect artefacts for their film projects. When they are photographed together at home or away, the shots are always carefully posed showing them immaculately dressed. They are not intimate candid shots; they are deliberately presented to discerning viewers and fans. Like the costume photographs and portraits, these shots are theatrical. They tell stories in which the subjects perform identities. The emphasis on costume, setting, props, accessories, and body language – the artifice of the scene – create performative events that are driven by design.

Hollywood’s bohemian New Women: Rambova and Nazimova

Rambova’s admiration for and identification with Russian culture was not unusual at the time. Russian art, especially dance, was influential in the US and the Ballets Russes’ style of Orientalism was in vogue. According to Studlar, it had far-reaching effects on Hollywood’s visualisation of Orientalism and on performance styles. [30] Although the ‘Russian vogue’ preceded the First World War, following the 1917 revolution many Russian émigrés went to Hollywood, where the fashion for Russian themes and stories created a demand for their historical knowledge and experience. During the 1920s cultural exchange between Russia and the US flourished and several high-profile Russian artists, writers, and musicians worked in Hollywood, though their experience was not always happy. [31]

Some Russian émigrés fared better than others. Rambova’s mentor Kosloff, a Ballets Russes alumnus and successful dance coach in Los Angeles, developed a thriving career as a character actor thanks to his association with Cecil B. DeMille. Alla Nazimova, an actress with Stanislavski’s Moscow Art Theatre, moved to New York in 1905 and became a major Broadway star before making her screen debut in 1916, when she joined Metro Pictures in Hollywood. An actress, writer, and producer, she became a powerful figure in the industry with her own production company. Like many émigrés in Hollywood, Nazimova had an élite circle of friends and associates who acted out a bohemian existence off screen as well as in movies. At her Garden of Alla residence, its interior decorated à la chinoise, [32] Nazimova mounted exotic costume parties inspired by Orientalism in which she and her entourage apparently acted out daring erotic scenarios. Within her international group, sexual experiment and fluid gender boundaries were taken for granted. Nazimova was thought to be predominantly lesbian, although she had relationships with men, and bisexuality was common in the clique. [33]

In “Fashion/Orientalism/The Body,” Peter Wollen describes the Thousand and Second Night party thrown by Paul Poiret in 1911 to launch his new collection of oriental fashion designs, which included daring “harem pantaloons” as trousers for women.

Figure 8 – Denise and Paul Poiret perform as sultan and female slave at the Thousand and Second Night party, 1911. Photo uncredited.

At the party, Poiret was dressed as a sultan and his wife Denise wore a dress whose skirt resembled a minaret (figure 8). She and her women attendants were confined in a golden cage from which Poiret released them. The scene took place in a phantasmagoric Eastern setting of excess and extravagance. [34] At this party, Poiret performed the part of despotic ruler of female slaves; later he described his role of master as ruled by the dreams and desires of women who perceived themselves as slaves. Wollen concludes that Poiret’s conception of the master-slave dialectic can only be overcome when “the slave is able to read and to write the signs of her own desire and to retextualise her own body.” [35] If the stories about Nazimova’s appropriation of Orientalist masquerade balls are to be believed, they provided a theatre for the revision of the master-slave dynamic by privileging the performance of women’s desire, reflecting wider cultural trends. By writing the signs of that desire on male and female bodies, Rambova’s designs participated in this cultural shift.

Rambova met Nazimova through Kosloff. Rambova produced uncredited designs for Kosloff’s projects with Cecil B. DeMille. Kosloff apparently offered his services as set and costume designer to Nazimova, who agreed to try him out on her planned production of Aphrodite. Rambova delivered the sketches, which were her own, and, the story goes, Nazimova immediately recognised her talent. She took on Rambova as art and costume designer for her production company and their intense creative partnership began. [36] There has been speculation that they also had a sexual relationship, although there is no reliable evidence to support the idea. Leider leaves the question open, stating that in the climate of sexual freedom, many heterosexuals experimented with bisexuality. [37] Rambova and Nazimova shared a fascination with Orientalism, European style, theatrical self-presentation and Decadent art, and their partnership was close. Nazimova was certainly much taken with Rambova.

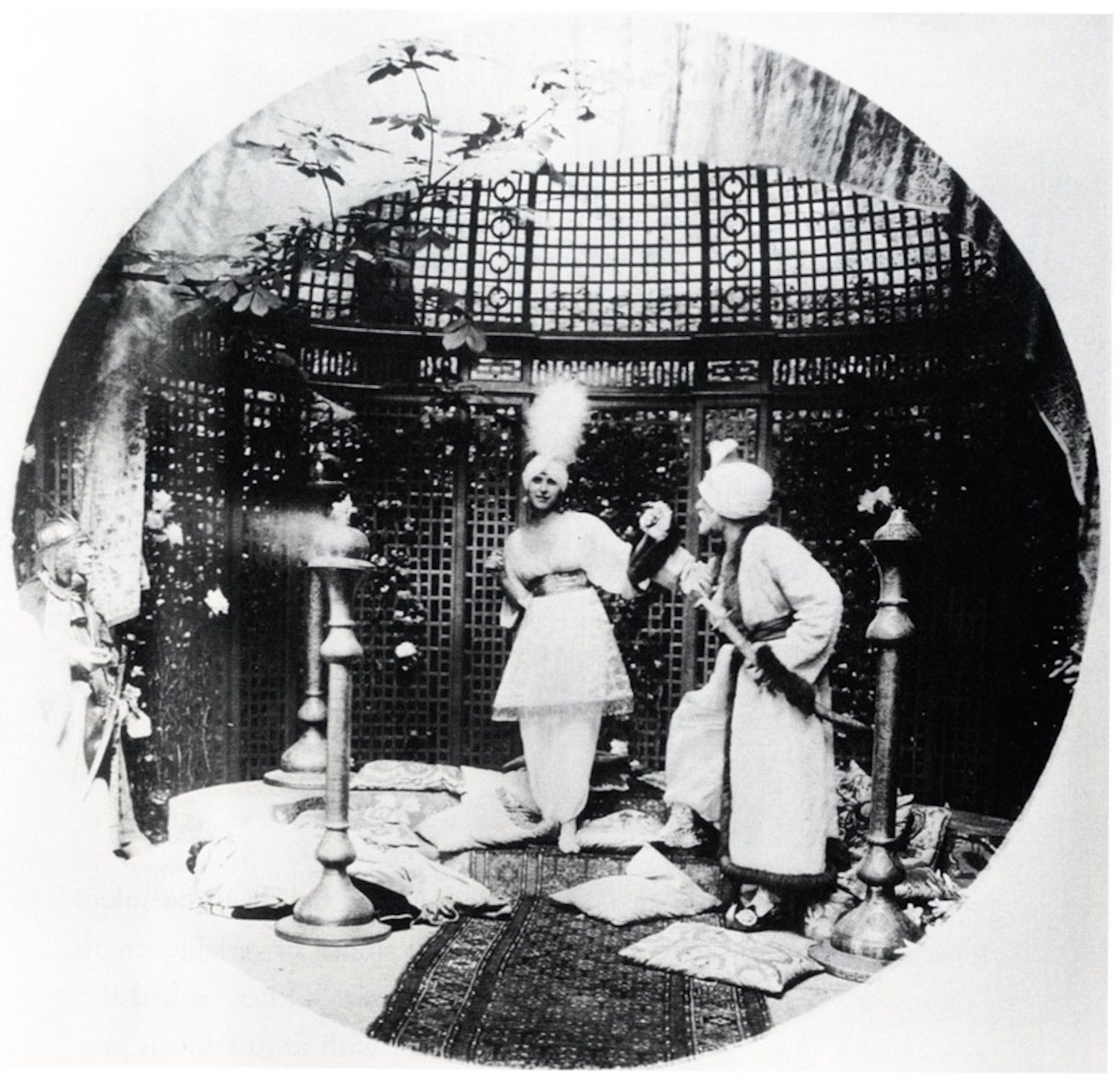

Aphrodite was shelved by Metro for censorship reasons, and their first collaboration was Camille. The production updates the popular novel La Dame aux Camelias to the twentieth century. Nazimova stars as consumptive courtesan Marguerite Gautier and Valentino plays her naïve young lover Armand Duval. Valentino is overshadowed by Nazimova’s performance, which renders the doomed Marguerite through exaggerated poses and gestures that match Rambova’s abstract designs, which dominate the film (figures 9 and 10). [38]

Figure 10 – Shades of Klimt: Nazimova in Rambova's costume design for Camille. Photograph by Arthur Rice, 1921.

Camille’s spectacular visual design is an early example of Rambova stamping her signature on the productions in which she was involved. It also demonstrates the leading role played by design in marking a film as art during the period. Actors, sets, and costumes form part of a cohesive design scheme, and the influence of European art cinema is evident in the borrowing of styles from German Expressionism and decorative modernism. The set includes nods to Erté and Art Deco, and Nazimova’s costume quotes Charles Rennie Mackintosh (the image in figure 10 also has overtones of Gustav Klimt). The overarching architectural motif is circular, echoed in the stylised camellias that adorn the sets and costumes. This motif is primarily associated with Marguerite, and is so prevalent that it seems to inscribe female sexuality and seductive power into the texture of the film.

Although she dies at the end, Nazimova’s Marguerite controls the narrative and her performance is diva-esque. The production’s exotic ‘look’ and the dark themes of sex and death evoke European art cinema rather than Hollywood, and Nazimova is in stark contrast to fair-haired American stars such as Mary Pickford. Camille was not a critical or box office success; many critics saw it as too avant-garde for popular audiences. It remains a strong statement of Rambova’s style and preoccupation with projecting a persona that was, in more senses than one, foreign to prevailing ideas of femininity. [39]

Camille’s self-conscious homage to European cinema and art movements is one instance in which the contribution of European artists and technicians to the Hollywood industry is recognised. However, despite the high regard in which European culture was held, European-derived stories and ideas were often thought too dark and were adapted by Hollywood producers to suit the tastes of American audiences. There was a demand for art films, and the industry looked towards international markets, but Camille’s reception suggests that it was too high-brow to find a domestic audience. While some appreciated the film’s artistry, it was perceived as an eccentric work of ideas. [40] Throughout her film career, Rambova aspired to work on such challenging artistic productions and fought for creative control. She is said to have influenced Valentino to do the same, provoking his conflicts with market-led studio bosses.

Reimagining Salome

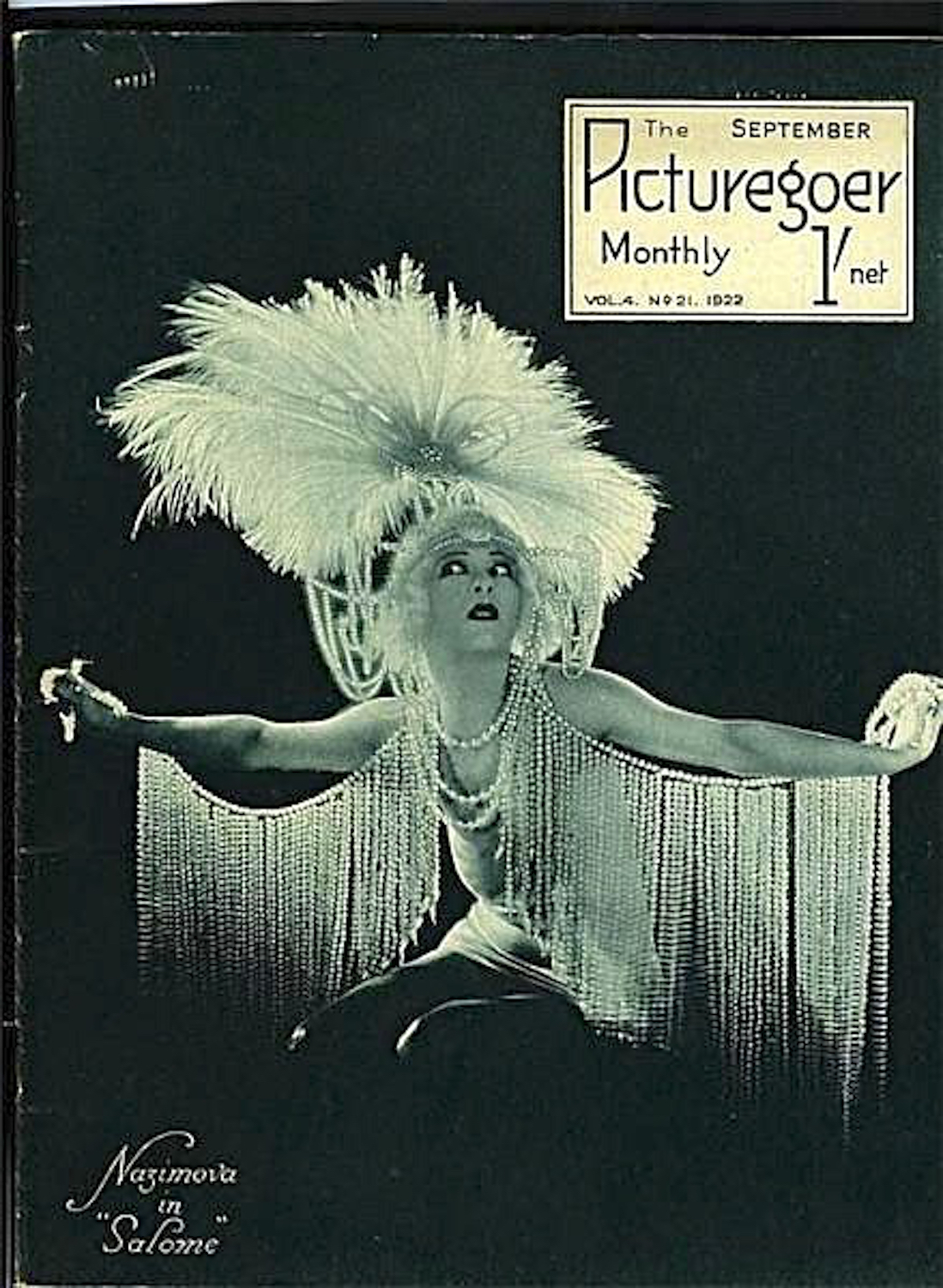

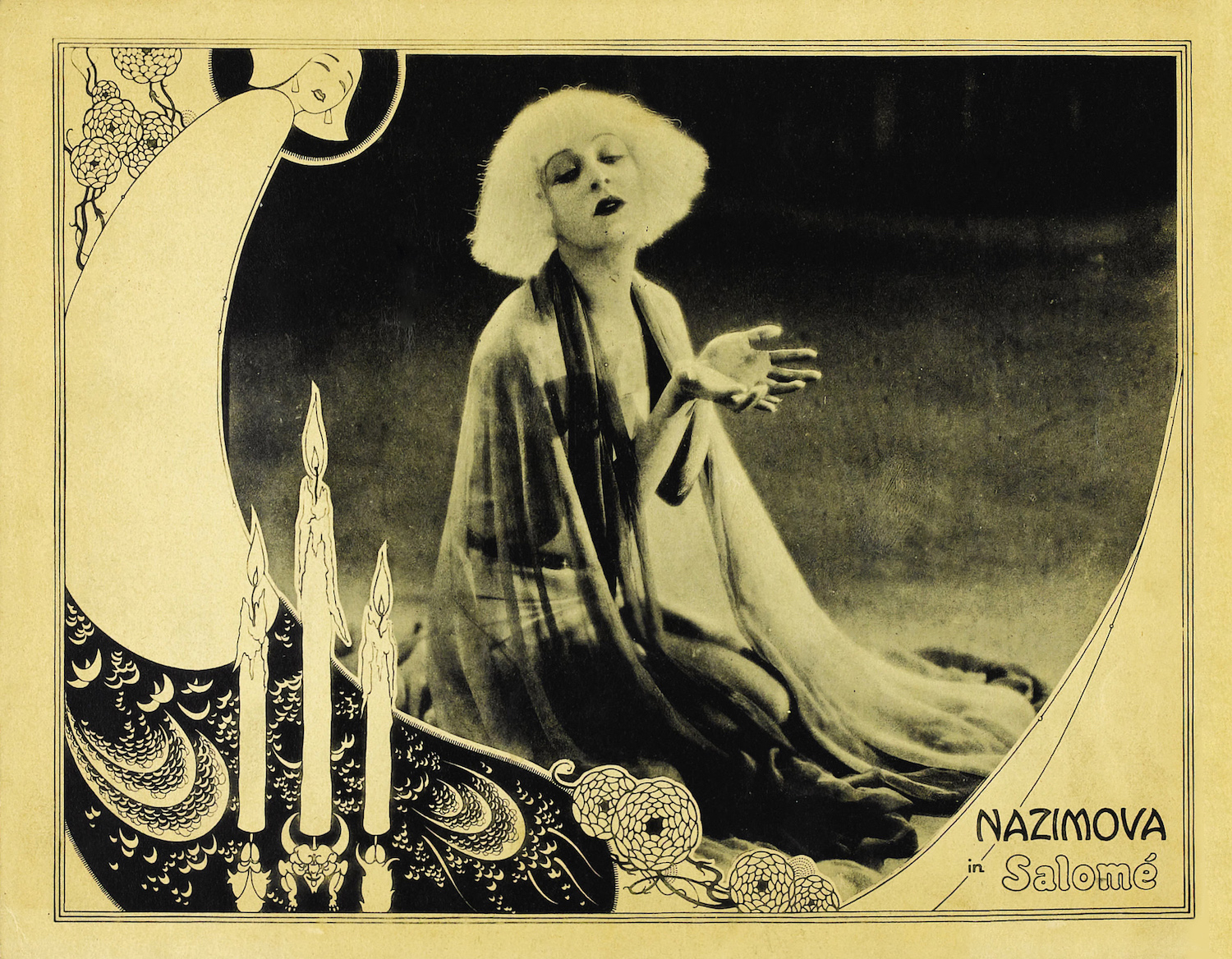

Rambova acted as art director and costume designer on Nazimova’s production of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1922). Their next collaboration was Salome (1923), an extraordinary interpretation of Oscar Wilde’s play for which she drew on Aubrey Beardsley’s decadent illustrations, which visualised themes of deviant desire (figure 11).

Figure 11 – Rambova's designs for Salome echo Aubrey Beardsley. Lobby card for the film, 1922. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

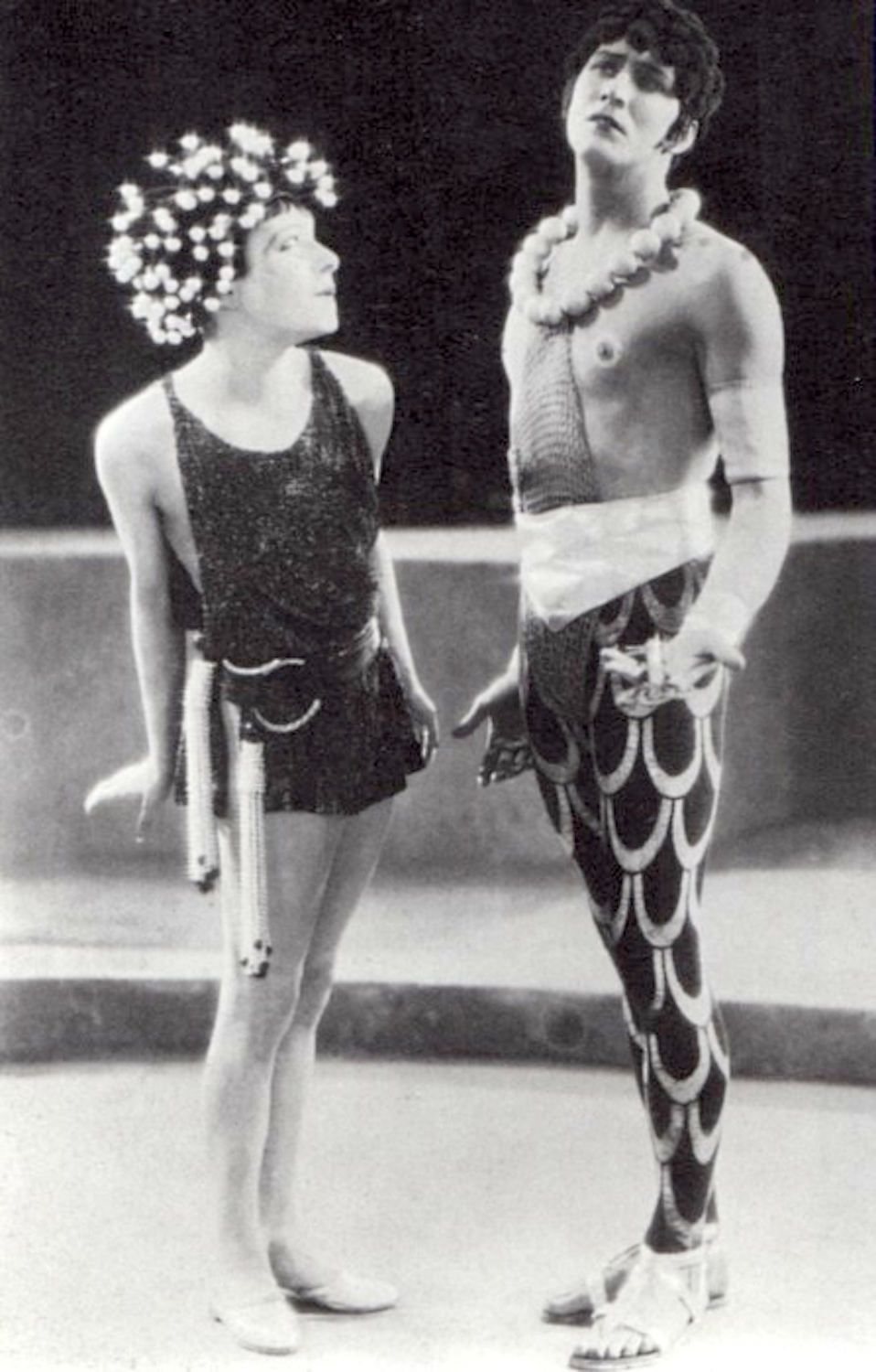

Like Camille, Salome has a unified design concept. Certain motifs recur in sets and costumes and the stylised performances work in tandem with the design, which is overpowering. Nazimova wears skimpy, revealing costumes and models her performance style on art-dance. [41] Popular renditions of Salome often portrayed her as an orientalised vamp. Rambova uses Orientalism in her designs (Nazimova wears a turban and see-through harem pants in the beheading scene), but her Salome seems to be inspired by dancers such as Loie Fuller, Ruth St Denis or Isadora Duncan, who celebrated the freedom and mobility of the female body and danced barefoot.

Rambova’s designs for Salome undoubtedly contribute to its reputation as a queer text. For David E. James, the film’s excessive stylisation in sets, costume, and performance radically breaks with developing codes of realism in narrative. [42] He sees Nazimova’s Salome as a femme fatale, pointing to the redistribution of gender positioning and the interruption of conventions of narrative, and claiming that the film can be understood as “a homosexual subculture’s reconstruction of film grammar for its own expressive needs and pleasures.” [43] In her study of the film, Patricia White similarly argues that Rambova’s visual design “amounts to full collaboration in the film’s [...] unmistakable homoeroticism.” [44] She uses the central metaphor of the veil to claim that Nazimova’s identity and agency is obscured by her gender and the tendency to present her as spectacle. [45]

I would argue that Rambova’s use of the sexual symbolism of pearls in her Salome costume designs unveils female agency and places it centre stage. White mentions the pearls in connection with consumerism, but her focus is on Nazimova’s star performance as an appropriation of Wilde’s text, rather than on the design. Yet, as her discussion of the infamous “Cult of the Clitoris” furore surrounding Maud Allan’s stage rendition of Salome intimates, [46] Rambova’s distracting use of pearls can be seen as an overt visualisation of female sexuality and lesbian desire, written across male and female bodies. It is surprising that this bold design statement, which reconfigures male homosexuality as non-phallic, has gone unnoticed by scholars or has been received as camp by other commentators.

Figure 12 – Reinventing sexuality: Rambova's use of pearls in costumes for Salome. Still undated and uncredited.

In this image from the film, Nazimova looks like a boy (figure 12). Her costume has appendages made of pearl garlands, secured by strings of pearls, and her headdress is made of oversized pearls. The pearls around Earl Schenck’s neck are even more enlarged and his costume is reminiscent of Nijinsky. Other male characters also wear oversized pearls, which accentuate the androgyny of the mise-en-scène. The detachable and interchangeable nature of costume accessories such as belts, head- and neckwear contributes to the gender slippage.

Rambova’s outlandish use of pearls in Salome echoes the work of Russian-born designer and illustrator Erté, who featured pearls, including oversized ones, extensively in his costume and fashion designs (figures 13a and 13b). Pearls were a common element of Art Deco, and though it is difficult to attribute any direct influence by Erté on the production, there are some striking similarities.

In the Erté design on the right, the association of pearls with female sexuality is explicit as a garland of pearls surrounds a suggestive inscription on the dancer’s abdomen and inner legs. In the context of the film’s enactment of symbolic castration, with Salome demanding the beheading of the prophet Jokanaan, the pearls can be taken to intimate non-phallic sexuality. Jokanaan is imprisoned in a cage from which Salome releases him, in an inversion of the sultan-female slave dynamic. Although, like Marguerite in Camille, Salome dies at the end, the narrative is driven by her desire. Her appropriation of the gaze and power over the male characters projects a compelling fantasy of female dominance. Rambova’s designs articulate this fantasy, dividing the set into two opposing spaces between which Salome moves in her quest to emasculate both her stepfather King Herod and Jokanaan.

The film was marketed as a version of Oscar Wilde’s play indebted to Beardsley’s illustrations. However, Rambova’s designs are not Beardsley imitations. She combines many influences to produce new interpretations of female and male identities, using costume to reinvent the body and creating an arena in which gender fluidity is performed. Salome’s overt emphasis on design and performance is a tribute to the expressive power of both. While some critics admired this aspect, the film received mixed reviews and was not a commercial success, although it has since acquired a cult reputation. [47]

A woman of influence

Rambova’s daring sets and costumes for Salome enhanced her profile as a talented designer with a distinctive personal style. However, her reputation was closely tied in with Valentino’s, and it was dented by their damaging conflict with Famous Players-Lasky. According to Leider, Monsieur Beaucaire (1924) was intended to redeem this situation by restoring Valentino’s popularity and showcasing Rambova’s design skills. [48] In spite of the studio’s financial difficulties, the film had a huge budget, much of which was devoted to costume, jewellery, wigs, props and a large cast. [49] The production was promoted on its visual design: in May 1924, Motion Picture Magazine had an article reporting from the New York set that the legal difficulties between star and studio had been resolved, detailing the extravagance of sets and costumes. [50]

The following month the magazine ran an illustrated feature on the film with photographs by Russell Ball displaying the lavish designs. [51] It would be an art film and, although Rambova’s contractual arrangements remain obscure, it appears she had considerable artistic control over the entire project, acting as uncredited assistant director as well as art director and costume designer. The feature’s inclusion of a sketch of Rambova sitting next to director Sidney Alcott on set alludes to her role in such terms. [52] Leider maintains that she asked to be addressed as Madam and opinion among the cast and crew was divided as to whether she “interfered” too much. [53]

Beaucaire would also be a very European production, in line with the Valentinos’ sophisticated brand. Rambova worked with French art deco designer and illustrator Georges Barbier, who was based in Paris and sent his designs from there. The August 1924 issue of Motion Picture Magazine included a page of his sketches with photos of the actors wearing the costumes. [54] Rambova was also responsible for some of the costumes. She carried out extensive research in Europe for the production and is reported to have invited acclaimed Moscow Art Theatre director Konstantin Stanislavski to visit the set. [55] As with Rambova’s other projects, the design is dominant and defines the stylised acting, with Valentino’s witty send-up of his sex-god image the star turn.

The flimsy story revolves around masquerade, as Valentino’s duke disguises himself as a humble barber to escape the wrath of Louis XV. The acting is histrionic, almost choreographed, and the entire production is enacted as a piece of theatre in which performance is everything. There is much play with gender and the look as Valentino’s character is the object of both male and female gaze. He is dandified, heavily made up with eye shadow and lip rouge, and sports a beauty spot. As he sings to Bebe Daniels in an early scene, she turns her head away and an inter-title appears: “The shock of his life – a woman is not looking at him!”

The fetishism of Monsieur Beaucaire’s costumes is evident in production stills and promotional materials, which emphasise the theatricality of the performances (figures 14a and 14b). High-key lighting creates shimmer on fabric, hair, and skin, picking out the complexity of costume and accessories and eroticising the image. Highlighting costume in this way draws attention to the lavish production values, and also emphasises the artifice of class and gender performance. Commodity fetishism is evident in this spectacular display; it is the images themselves that incite libidinal desire and arouse fantasies of possession and control in viewers.

Fetishism’s long and chequered history in feminism and moving image studies is beyond the scope of this article. Psychoanalytic conceptions that position it as a refusal of female difference have been extensively revised. Fetishism has been rethought as a structure of disavowal that enables the recognition of sexual difference even as it attempts to occlude it. [56] In my view, Rambova’s work for film displaces fetishism’s phallic regime by foregrounding female sexual imagery, and by exploiting costume’s potential to visualise the mobility of phallic power between genders, as noted in relation to Salome. This enables fantasies of empowerment and control in viewers, a notion that is particularly appropriate to the fan’s wish to possess their object of desire. For Valentino’s female and male fans, Monsieur Beaucaire’s production stills offer access to an imaginary eroticised world, and also provide an aesthetic experience that invites their perception of artistry and beauty. This combination of eroticism and aestheticism is characteristic of Rambova’s designs.

Despite receiving critical praise for its pictorial qualities, Monsieur Beaucaire did badly at the domestic box office outside the main urban centres, [57] though it was enthusiastically received in London and Paris. [58] Although the box-office returns were respectable they did not recover the exorbitant costs of mounting the movie, the blame for which was put on Rambova’s profligacy. She worked on three more Valentino projects before they separated: A Sainted Devil (1924), now lost; The Hooded Falcon, loosely based on the legend of El Cid, for which she did extensive preparation, though the film was never made; and Cobra (1925). By all accounts, she demonstrated her usual meticulous research and attention to detail and exercised considerable control over production. [59] She had a say in the script, casting and choice of director and recruited new talent in the form of up and coming designers Gilbert Adrian and William Cameron Menzies, as well as contributing her own designs. [60] She and Valentino travelled to Europe to collect clothes, props, and artefacts that would add authenticity to the productions, paying little attention to the cost.

Backlash

Despite their public denials, stories about Rambova’s dominance of Valentino and her damaging interference on set escalated, fuelled by his fondness for the ‘slave bracelet’ she gave him in 1924, which was perceived as a symbol of his subservience. [61] In March 1925, Variety ran a front-page story, tellingly titled “Mrs. Valentino Cause of Break with Williams,” about disagreements between the Valentinos and Ritz-Carlton producer J. D. Williams in which he faced them with an ultimatum that Rambova should cease to interfere in productions. [62] Valentino defended her, but later accepted a contract with United Artists that excluded Rambova from playing any part in his career. [63] This betrayal effectively marked the end of the relationship.

Following her split with Valentino, she worked on her own production, a satire of the beauty industry starring Nita Naldi titled What Price Beauty? (1925), now lost, which she wrote, produced and acted in. [64] In October 1925 Variety reported that she had signed a contract to appear in four pictures to be made in the next year, and would also play in vaudeville. [65] Film Booking Offices of America would only take up the four-picture option if the first title performed well. [66] Rambova’s stilted acting in When Love Grows Cold (1925) was badly received and it can be assumed that FBO did not take up the option, although the reason generally given for Rambova’s exit from the film industry is her disgust at the company’s cynical exploitation of the end of her marriage. [67]

In 1928, aged thirty-one, she opened a fashion studio in New York City and ran a successful couture business for a celebrity clientele until 1931, when the worsening economic climate in the US forced her to close and move to France. Her fashion designs reflected the preoccupation with exoticism and Orientalism that characterised her film work and her personal style. [68] She was a lifelong collector of cultural artefacts, and in later life developed a scholarly interest in comparative religion and symbolism. Her extensive archive, including her unpublished manuscripts, is currently held by Yale University. [69] In 1928 she wrote an unproduced three-act play, All That Glitters, based on her experiences in Hollywood. Her film work and her later career testify to her creativity, flair for innovation and business sense, and above all to her understanding of design’s definitive role in producing performance and identity. Like the decorative modernist artists who inspired her, Rambova was an iconoclast. Her work on and off screen enables different ways of thinking about the role of design and performance in cinema and in moving-image culture.

Rambova participated in a performance culture that visualised women’s power and agency to an unprecedented degree. Her confident persona as a New Woman was acted out off screen and in film designs that asserted a feminine perspective and aesthetic, often against the grain of narrative, as in Camille and Salome. While her experience in the film industry exposes the limits of female control, she, along with other successful women filmmakers, was able to exert considerable influence for a time. My account of Natacha Rambova sees her as a character projected through performance whose story is reimagined by others, including myself, from visual and text-based objects that require deciphering. In the same way that reading written documents or films demands specialist skills, such critical engagement involves expertise in theories of performance and design. This interpretive approach declines to take media artefacts as neutral, transparent vehicles for factual information. Instead, it acknowledges that historical documents are often fictional representations, and that knowledge, rather than being embedded in materials themselves, is produced from competing interpretations. I have analysed some of the representational strategies through which Rambova is pictured in images and texts, not in order to discount the reality of her existence, but to highlight the key role of performance and design in the processes of reconstructing and reformulating moving-image history.

Endnotes

[1] See Drake Stutesman, “Natacha Rambova,” Women Film Pioneers Project at Columbia University: https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/pioneer/ccp-natacha-rambova/. See also Gaylyn Studlar, “‘Out-Salomeing Salome’: Dance, the New Woman and Fan Magazine Orientalism,” in Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar, eds., Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 119-23. Rambova is given substantial coverage in Emily W. Leider’s Valentino biography Dark Lover: The Life and Death of Rudolph Valentino (London: Faber and Faber, 2003).

[2] Rambova’s work with Alla Nazimova is mentioned by Studlar in “‘Out-Salomeing Salome’,” 123, who cites Maureen Turim on costume design in Camille: “Seduction and Elegance: The New Woman of Fashion in Silent Cinema,” in Shari Benstock and Suzanne Ferris eds., On Fashion (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1993), 156. Patricia White, “Nazimova’s Veils: Salome at the Intersection of Film Histories,” in A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema, eds. Jennifer M. Bean and Diane Negra (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2002), 60-87, also discusses Rambova’s collaboration with Nazimova.

[3] The concept of branding is not usually applied to the silent period, but it has the advantage of drawing attention to the circuits of publicity and reception that forged Rambova’s celebrity identity. Mark Lynn Anderson discusses the manufacture of star identities in response to market demands and changes to the 1920s star system in Twilight of the Idols: Hollywood and the Human Sciences in 1920s America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 79 ff.

[4] Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (London: Penguin Books, 1990), 26-7.

[5] Goffman, The Presentation of Self, 34.

[6] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 59-74; Marjorie Garber, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety (New York: Routledge, 1997), 355-356.

[7] For example, “Settings à la Ballin,” featuring set designs by renowned muralist Hugo Ballin, Motion Picture Magazine, November 1922: 63. For ornamental graphics, see Contents page, Motion Picture Magazine, August 1919: 17.

[8] Brett L. Abrams, Hollywood Bohemians: Transgressive Sexuality and the Selling of the Movieland Dream (Jefferson N.C.: McFarland, 2008), 78-112.

[9] Anna Prophater, “Rodolph Valentino and Marriage,” Screenland, October 1923: 22-23.

[10] Leider, Dark Lover, 137.

[11] Ruth Waterbury, “Wedded and Parted, or, in other words, the story of Natacha Rambova Valentino,” Photoplay, December 1922: 58-9, 117-19.

[12] Waterbury, “Wedded and Parted,” 58-9.

[13] Waterbury, “Wedded and Parted,” 119.

[14] Gaylyn Studlar, “‘Optic Intoxication’: Rudolph Valentino and Dance Madness,” in This Mad Masquerade: Stardom and Masculinity in the Jazz Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 192.

[15] Studlar, “Optic Intoxication,” 192.

[16] Leider, Dark Lover, 185.

[17] “All May Now Wear Pearls”: advertisement in Motion Picture Magazine, May 1923: 111.

[18] Studlar, “Out-Salomeing Salome,” 105, quoting Sumiko Hagashi, Cecil. B. DeMille and American Culture: The Silent Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 104.

[19] Leider (Dark Lover, 58) claims that Rambova designed Valentino’s costumes for The Sheik, though this is uncorroborated.

[20] Leider, Dark Lover, 216.

[21] Studlar, “Optic Intoxication,” 151, 179.

[22] For a discussion of the undecidable nature of Valentino’s image, see Anderson, “Queer Valentino,” in Twilight of the Idols, 70-126.

[23] Garber, Vested Interests, 361.

[24] Studlar, “Out-Salomeing Salome,” 105-22.

[25] Studlar, “Out-Salomeing Salome,” 125.

[26] Leider, Dark Lover, 135.

[27] Paul Iribe published a limited edition of thirty photographs of Nijinsky by Adolph de Meyer in 1914. See Leider, Dark Lover, 186.

[28] “Natacha Valentino Inspired Paul Poiret to Create for Her this Exotic Wardrobe,” Photoplay, January 1924: 42-43.

[29] See Studlar, “Out-Salomeing Salome,” 99-129.

[30] Studlar, “Out-Salomeing Salome,” 116.

[31] Harlow Robinson, Russians in Hollywood, Hollywood’s Russians: Biography of an Image (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2007), 35-39, 45.

[32] “Mme. Nazimova Has Handsome New Home,” Los Angeles Times, 2 February 1924: A9. Available online: http://www.allanazimova.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/LAT-19240202-Nazimova-builds-second-home.pdf. Accessed 13 April 2015.

[33] Leider, Dark Lover, 133-134.

[34] Peter Wollen, “Fashion/Orientalism/The Body,” New Formations 1 (Spring 1987): 10-13.

[35] Wollen, “Fashion/Orientalism/The Body,” 29.

[36] Leider, Dark Lover, 132.

[37] Leider, Dark Lover, 133-4. Hilary Hallett, Go West, Young Women!: The Rise of Early Hollywood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 143, features an image of Nazimova and Rambova sitting together on a bed, dressed in Chinese-style pyjamas, that plays with the idea that they were lovers.

[38] Rambova’s designs for Camille quote Erté (top, figure 9) and Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

[39] Leider, Dark Lover, 156-7.

[40] “Camille,” Variety, 16 September 1921: 35; Moving Picture World, 24 September 1921: 446; cited by Leider, Dark Lover, 136.

[41] Studlar, “Out-Salomeing Salome,” 123.

[42] David E. James, “Salome,” in The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 31.

[43] James, “Salome,” 32.

[44] White, “Nazimova’s Veils,” 65.

[45] White, “Nazimova’s Veils,” 69.

[46] White, “Nazimova’s Veils,” 80.

[47] See Salome review in Variety, 5 January 1923: 42; Adele Whiteley Fletcher, “Across the Silversheet: Talk Concerning the New Productions,” Motion Picture Magazine, October 1922: 65, 116; “Photoplay’s Selection of the Six Best Pictures of the Month,” Photoplay, August 1922: 61.

[48] Leider, Dark Lover, 295-305.

[49] Dorothea B. Herzog, “Valentino Returns to Screen in Million Dollar Picture” Movie Weekly Magazine [US] 31 May 1924: 8-9. The bill for costumes was said to be $90,000.

[50] “The Editor Gossips,” Motion Picture Magazine 27 (4), May 1924: 108-10.

[51] “The Prodigal Returns,” Motion Picture Magazine 27 (5), June 1924: 20-2.

[52] “The Prodigal Returns:” 21.

[53] Leider, Dark Lover, 299.

[54] “The Designer’s Dreams Come True,” Motion Picture Magazine 27 (7), August 1924: 30.

[55] Gavin Lambert, Nazimova: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1997), 271.

[56] For example, Emily Apter, Feminizing the Fetish: Psychoanalysis and Narrative Obsession in Turn-of-the-Century France (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991); John Ellis, “On Pornography,” in Peter Lehman, ed., Pornography: Film and Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 38-45.

[57] “Monsieur Beaucaire,” Variety, 13 August 1924: 19.

[58] Leider, Dark Lover, 303.

[59] Margaret Norris, “Behind the Screen with Two Greenhorns,” Motion Picture Magazine, 28 (8), September 1924: 84; Leider, Dark Lover, 308-312.

[60] Leider, Dark Lover, 311, 323.

[61] John P. Miles, “Sheik Valentino’s Tent Mate Touchingly Denies That Rudy is Henpecked,” Independent [St. Petersburg, PA.], 24 June 1925: 20. Leider, Dark Lover, 324-325.

[62] “Mrs. Valentino Cause of Break with Williams,” Variety 77 (3), 4 March, 1925: 1, 58.

[63] Leider, Dark Lover, 334-335.

[64] Leider, Dark Lover, 335, 339.

[65] “Mrs. Valentino Returning,” Variety, 14 October 1925: 38.

[66] “Dr. Goodman Supervising,” Variety, 11 November 1925: 31.

[67] Leider, Dark Lover, 351.

[68] Heather Vaughan, “Natacha Rambova: Fashion Designer 1928-31,” Dress 33, 2006: 33.

[69] The Natacha Rambova Archive at Yale University: http://www.yale.edu/egyptology/rambova_scholarship.htm. Accessed 12 February 2015.